Tailoring Treatment

Hypoglycemia significantly increases patients’ risk for injury and death.1 Data from several large trials (ACCORD, ADVANCE, VADT) provide evidence demonstrating the association between severe hypoglycemia and increased risk of subsequent mortality.1 Although severe hypoglycemia is common in older adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, patients with type 2 diabetes tend to have longer hospital stays and greater medical costs.1 Rates of severe hypoglycemia are more common among older adults, those with other chronic conditions (ie, CKD, CVD, CHF, depression, and higher HbA1c levels), and those who are on insulin or taking secretagogues.1,2 For type 2 diabetes, early-course treatment usually involves metformin in addition to lifestyle changes. As the disease progresses and additional therapies are warranted, the risk of hypoglycemia increases depending on the agent used (especially in the presence of comorbidities).2

The major goals of hypoglycemia treatment are to identify treatable and modifiable causes (ie, medication used) and to implement strategies aimed at risk reduction.2 The fear of hypoglycemia, or actual hypoglycemia, remains a significant barrier for patients (and their health care providers) trying to reach their recommended glucose targets.1,2 Medication adjustments from oral agents that pose the greatest risk of hypoglycemia (ie, sulfonylureas) to other newer classes such as newer generation basal insulins, GLP-1 RAs, and SGLT-2 inhibitors should be considered in patients either at elevated risk or who have experienced an event.

Cognitive Impairments and Dementia

Diabetes is associated with a significantly increased risk of dementia and cognitive decline. Compared with patients without diabetes, a recent meta-analysis found that type 2 diabetes was associated with a 73% increased risk of all types of dementia, 56% increased risk of Alzheimer dementia, and 127% increased risk of vascular dementia.3 Additionally, the ACCORD trial found that patients with poor cognitive function are more likely to experience episodes of severe hypoglycemia.4 Tailoring glycemic therapy may help to prevent hypoglycemia in individuals with cognitive dysfunction. Insulin secretagogues, such as sulfonylureas and meglitinides should be avoided in this population.5

Anxiety Disorders

Patients with anxiety may have fears regarding diabetes complications, insulin or medication injections, not meeting blood glucose targets, and/or hypoglycemia. This anxiety may interfere with self-management behaviors and increase the risk of adverse events. Anxiety is common in people with diabetes and it is estimated that the lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety may be up to 19.5% of people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. A structured program of blood glucose awareness training delivered in routine clinical practice can reduce the rate of severe hypoglycemia in this population and improve HbA1c levels.5

Physical Activity

In individuals taking insulin or insulin secretagogues, physical activity may lead to hypoglycemia if the medication dose or carbohydrate consumption is not modified. These individuals may need to eat additional carbohydrates before exercising if their glucose level pre-activity is below 90 mg/dL. For some patients, hypoglycemia may occur after exercise and last for several hours due to increased insulin sensitivity. No routine preventative measures are usually advised for patients who are not treated with insulin or insulin secretagogues.5

Patient Education

Because of the high level of self-management diabetes therapy involves, communication is imperative to ensure that each patient is well informed and able to optimize their own care.2 One cannot assume patients are being educated elsewhere. Though evidence showing a clear correlation between the influence of self-management education and incidence/prevention of hypoglycemia is lacking, self-management education is proven to improve patient outcomes.1,2

Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) is an integral part of effective diabetes therapy and provides a tool for preventing hypoglycemia.5 The patient’s specific needs and goals should dictate the frequency and timing of SMBG or whether continuous glucose monitoring should be considered to prevent hypoglycemia.5 Consequently, it is important to realize the technology of glucose meters is sometimes challenging for patients and their caregivers. As glucose meters become more compatible for consumer use (smaller instrument size, additional readings besides glucose, upgraded older glucose meters), it is imperative for healthcare providers to ensure patients are well versed in how their glucose meter functions. Hypoglycemia, its risk factors, and its remediation must be discussed with all patients with diabetes, particularly those with a history of recurrent hypoglycemia and those with a risk of hypoglycemia who are on insulin or another antidiabetic agent.1

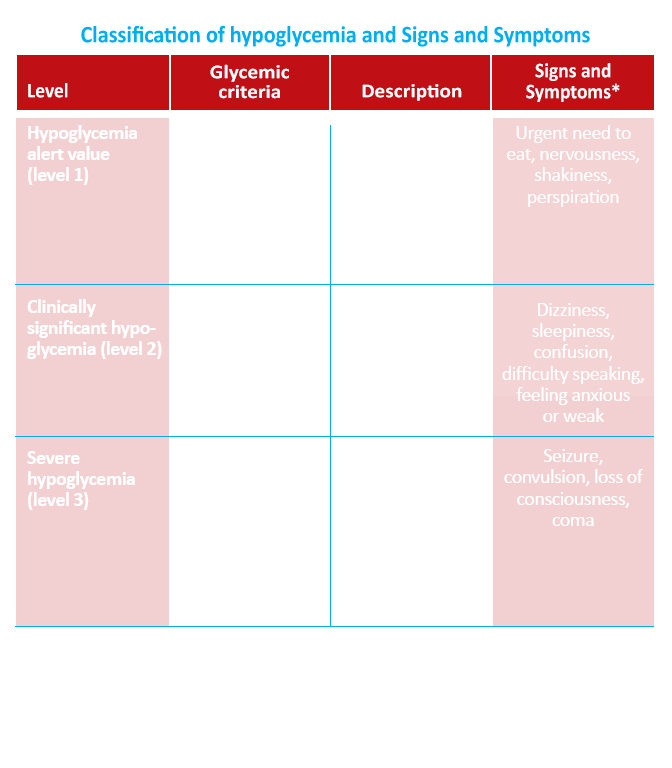

Patients, their caregivers, and their families must be aware of and educated about the signs and symptoms that indicate hypoglycemia (including nonspecific symptoms such as the Somogyi effect).2 Patients must also take responsibility for gaining a firm understanding of the SMBG reading, knowing whether and how to respond to the result, and being equipped with supplies enabling them to respond when appropriate.6

Evidence shows healthcare providers can do better in educating patients about how to respond to abnormal blood glucose readings.6 Knowledge of the currently available agents, their mechanism and onset of action, and most common side effects, especially the frequency of hypoglycemia, is a requirement for the health care provider to appropriately make this adjustment when necessary.

Self-Management of Hypoglycemia

Patients should be educated on ways to elevate their blood glucose levels during episodes of hypoglycemia. Glucose (15-20 mg) is the preferred treatment of hypoglycemia in conscious patients with blood glucose below 70 mg/dL. If glucose is not available, any carbohydrate that contains glucose will suffice. If SMBG still demonstrates hypoglycemia 15 minutes after consumption of glucose, the treatment should be repeated. Once SMBG shows normal blood glucose levels, a meal should be consumed to prevent recurrence of hypoglycemia.

In individuals with type 2 diabetes, protein intake may increase the insulin response to dietary carbohydrates. Patients should be cautioned to avoid using carbohydrate sources high in protein (such as milk and nuts) to treat or prevent hypoglycemia due to the potential rise in endogenous insulin.5 A simple and effective approach to glycemia management is emphasizing portion control and healthy food choices in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not taking insulin, who have limited health literacy, or who are older and at increased risk for hypoglycemia.5

Glucagon should be prescribed for all individuals at increased risk of level 2 hypoglycemia, defined as blood glucose below 54 mg/dL. Caregivers, school personnel, and family members should be instructed on how to administer glucagon if needed.

References:

- Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1384-1395.

- Evans Kreider K, Pereira K, Padilla BI. Practical approaches to diagnosis, treating and preventing hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:1427-1435.

- Gudala K, Bansal D, Schifano F, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of dementia: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:640-650.

- Punthakee Z, Miller ME, Launer LJ, et al. Poor cognitive function and risk of severe hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: post hoc epidemiologic analysis of the ACCORD trial. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:787-793.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S90-S102.

- Davis SN, Lastra-Gonzalez G (eds). Diabetes and low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:E2.